Actress Daniela Vega & Writer/Director Sebastian Lelio on Their Oscar-Nominated Film A Fantastic Woman

Chile-bred, Berlin-based director Sebastian Lelio has become an international filmmaker who moves between styles and countries. He’s also exceptionally prolific, with not one but three movies awaiting release. First up is A Fantastic Woman, one of this year’s five foreign-film Oscar contenders, which will be released today, Feb. 2, in the U.S. It’s the tale of a transgender woman, played by Daniela Vega, who fights for her right to grieve her older lover after his sudden death. Vega is the first openly transgender actress and model in Chile.

That movie will be followed by two English-language efforts, Gloria and Disobedience. The first, made in California and starring Julianne Moore, is a remake of the 2013 movie that established Lelio’s international reputation; it’s a study of an older woman’s search for new love. The second, based on Naomi Aldereman’s novel, features Rachel Weisz and Rachel McAdams as lovers whose relationship violates the code of London’s Orthodox Jewish community.

Lelio and Vega visited Washington in January to discuss A Fantastic Woman. Their interview with The Credits, which has been edited for length and clarity, covered many topics. (Vega spoke partly in English, and partly through a translator.) But given the subjects and themes of his last five movies, it seemed apt to ask if the director planned to build a career as a maker what were once called “women’s pictures.”

Lelio: Not at all. It happened. “Oops, I did it again,” I’m like Britney Spears in that sense. Now I connect the dots, looking backwards. I get asked, “Why did I make this trilogy about women?” But I’ve been just following what moves me, what thrills me. I see a film where no one else seems to be seeing a film. If you turn your camera toward your mother, there’s a film there. That was the case of Gloria. In this case, there is a film — beautiful, with great calligraphy — about a transgender woman in contemporary Santiago. It doesn’t need to be a rough, ugly-looking film. It can be a flamboyant, almost classical film. I’m not calculating the results, or coming from a place of having an agenda.

What do you mean by calligraphy?

Lelio: Cinema language. The film has a certain approach to the language, which is closer to classicism. That’s part of the game of the film. Because inside that is something that’s not classical. Which is the character, and the fact that Daniela is interpreting that character. That adds a new dimension to the film. Which a cisgender actor would not have been able to bring.

You’ve called A Fantastic Woman a “transgenre” film. What does that mean?

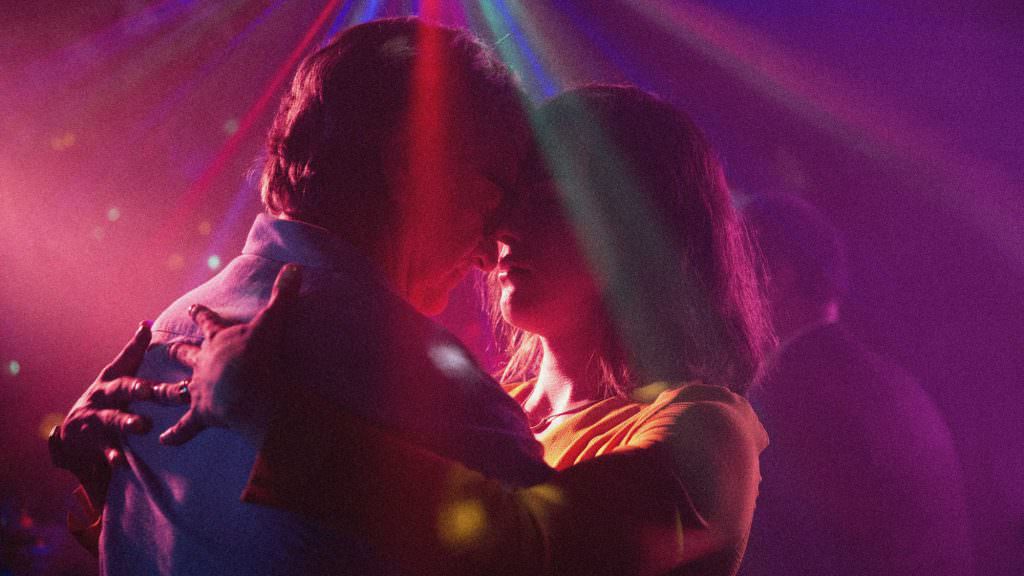

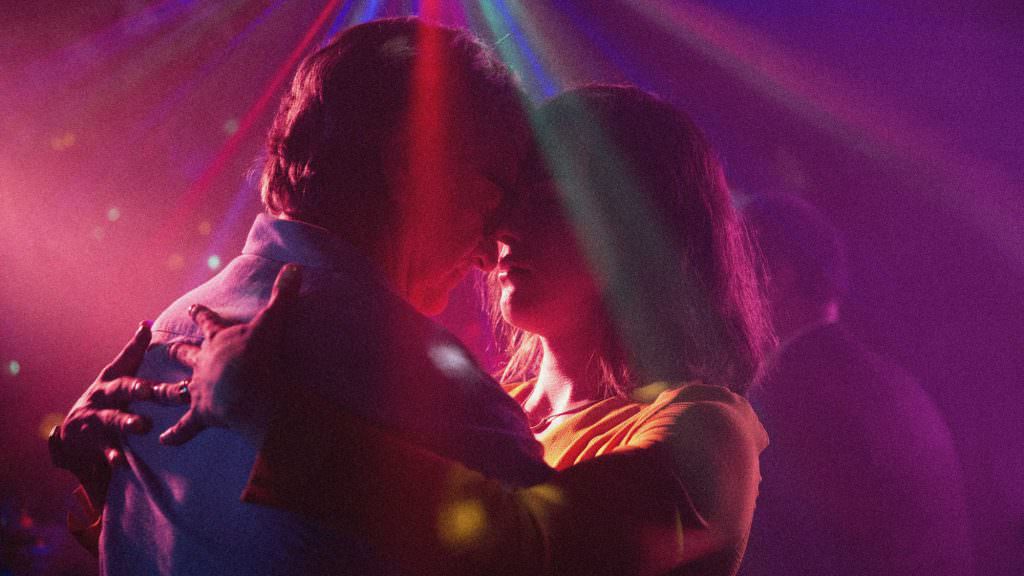

Lelio: That the film’s own identity oscillates among different tonalities and cinematic traditions, without being any of those separately. The film starts as a romantic film, but flirts with being thriller and becomes a ghost story. It becomes a character study, a film about a woman. Then a humiliation and revenge story. It’s a funeral film. It has few moments like silent cinema, like Buster Keaton and Busby Berkeley, in the windstorm sequence or the dance-floor scene. It’s this combination of identities that makes it transgenre. And that’s connected with its main subject, Marina. Who doesn’t want to be labeled in one easy gesture.

I didn’t want the film to be just one thing. I wanted it to be more slippery.

Is the remake of Gloria different thematically?

Lelio: It’s the same story. But it has a different energy because it’s a different woman. It’s a different culture, a different context.

You’ve directed two movies recently outside of Chile. A Fantastic Woman was made before you moved to Berlin. What is it that links the movie to Chile?

Lelio: Everything. It’s a story that emerges from Chile. It’s a very divided country. Everything is holy war in Chile. Everyday. I might be simplifying things, but half of the country is past-oriented, with a mindset still very close to what [former dictator Augusto] Pinochet meant. The other half is future-oriented and willing to embrace the complexity of life, In that tension, we exist. This film is settled exactly in that crack.

You started working with Daniela as a consultant. When did you realize that she would have bigger role than that.

Lelio: When I met Dani, I realized that I wanted to make the film. A film about this subject. Then I realized I was not going to make it without a transgender actress. Then toward the end of writing the first draft, it came to me: “Oh, she’s Marina. I don’t need to cast anyone. My dear friend, and cultural consultant, is the star of the film.” So when I had the first draft, I sent it to Dani. And asked if she would like to play the main role.

Vega: And I said yes immediately.

When you read the script, did you recognize yourself in the role?

Vega: It’s not based on me.

Right. But you were a consultant….

Lelio: She wasn’t a technical consultant at all. She wasn’t like a script consultant. It was more of a human conversation.

The character of Marina and her quest and perseverance suggest the films of Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardennes. Did you think of those?

Lelio: I did. I love their films. But I thought of them to try to stay away from that approach. That’s an approach that is realistic, grounded, attached to a painful reality. It’s the kind of cinema that has been very important, very influential, but that I didn’t want this film to have anything to do with.

If you see the camera style, and the color treatment, the things that are going on in the script, it’s not realism. You’re not in the Dardennes brothers universe or school. I would say this film is connected to older traditions, like ’40s and ’50 melodramas and women-centered films from the ’60s and ’70s.

One of the characters calls Marina a “chimera,” a mythological creature. Is that related to the ghost-story elements of the movie?

Lelio: A chimera is a combination of two impossible things. I think it’s half lion, half snake. So she’s insulting her in a very…educated way. Cultivated way. Something that not anyone can say. Does that connect with the ghostly dimension of the film? I think it does! It does in a strange way. I mean, there is a ghost in the film!

Vega: [showing an image she’s located via her smartphone] Chimera!

Lelio: There you go. So a lion that has two heads. Look at that! It’s a monster. It’s powerful.

But also a fantastic figure. Not a realistic figure.

Vega: It’s a product of the imagination.

Lelio: And that’s when the word “fantastic” plays a double role in the title. Is she fantastic because she has fantastic properties? Like she’s extraordinary? Or is she fantastic because she is the product of fantasy? I think the film leaves enough space for the spectator to decide.

Daniela, you’ve done singing and theater acting, but hadn’t been in a film before. How different is it playing to a camera rather than a live audience?

Vega: It’s very different. There’s only one eye looking to you. It’s as different as writing a letter to a friend, or writing a letter to a newspaper.

There’s scene where Marina is being photographed by the police, and has to disrobe. I was expecting a Crying Game moment, but it doesn’t happen.

Lelio: It’s too late for that. That was 25 years ago.

Vega: 26.

Lelio: We’ve all changed. That’s the beauty of cinema, because that was the right time for that gesture. Twenty-six years ago, we all went, “Oh my God!” Now no one would be shocked.

But, yeah, of course. It was a question. What do we do with that? The decision was to remain with the looks of others, and their reactions. There was something more violent in that gesture than in showing everything. I think the film is with Marina when it comes to that level of intimacy. It respects her.

To return to the idea of a “transgenre” film, is that harder to explain to a potential audience? From a marketing viewpoint, people always want to know just what kind of movie it is.

Lelio: That’s one of the subjects of the film. We need labels because they are like intellectual crutches. We need labels because we’re lazy. And labels are a way of not seeing the person. You just see a label. This film doesn’t have any message. But if it’s against anything, it’s against labels.