Talking to Eye in the Sky Director Gavin Hood

Entering a conference room in a downtown Washington hotel, South African director Gavin Hood is carrying a book about drones, which are central to his new film, Eye in the Sky. He's clearly fascinated by the technology, as well as the policy questions they raise. Hood mentions his pleasure in visiting D.C., where drone warfare is a matter of widespread professional interest. His previous movies include Rendition, a consideration of anti-terrorist policies that was partly set in Washington, and Ender's Game, which pondered war in a futuristic fantasy context.

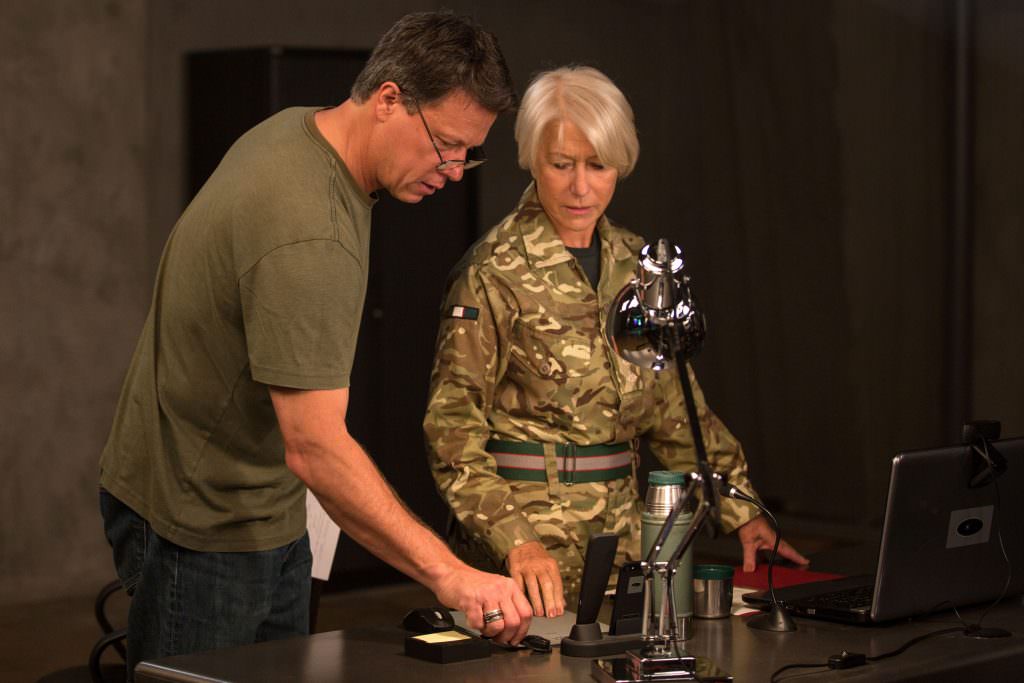

Eye in the Sky, in limited release as of March 11, stars Helen Mirren as a British colonel who sees a chance to eliminate some long-tracked terrorists from Somalia's Al-Shabaab group who've just been located in Kenya. For the missile strike, she relies on a Nevada-based American drone operator played by Aaron Paul, and needs authorization from a general (the late Alan Rickman) and several high-level British politicians (Jeremy Northam and Iain Glen). The intended attack is stalled when a little girl sets up a stand to sell bread next to the house the observation drones have targeted.

The film was shot in the director's homeland, and involved as much cutting-edge technology as the story it tells. Hood's interview with The Credits, which has been edited for length and clarity, begins with his explanation of the production's complicated logistics.

Ideally, I would have shot first everything that happens on the ground in Kenya, and then edited that footage and been able to project it on the screens, so all the actors knew what was happening. But for budget and scheduling reasons, we couldn't have all the actors on set at all times together. So Helen came in first, for her eight days or so, and worked against a green screen. She had to be satisfied with my describing to her what was happening. She said, "Gavin, I get paid to use my imagination. Don't worry. You just describe and let me know how it's going." She was wonderful to work with.

Helen left, and Aaron arrived. He was in his ground control station, and also had to work against green screens. And because I was trying to really get inside what he was thinking, I actually put the camera at certain points right in front of him. He plays into the lens of the camera. Alan Rickman and the team in COBRA — which is a real place, Cabinet Office Briefing Room A in Whitehall — whenever you see screens in there, there was actually nothing on them.

There are actually about 540 visual effects shots in this film, and I hope you don't notice a single one. But they were very complicated in terms of what's on which screen. What's on the right screen, the middle screen? My editor, Megan Gill, and I spent many hours just trying to pull all these pieces together.

The description of the way the actors worked reminded me of an animated film. Because the voice performers usually work alone.

I hadn't thought of it that way, but I guess that is a good analogy. I described the attack on the house so many times. I can remember on the last few days on set, thinking, "I cannot do this anymore. I cannot describe how this poor child can't move, is struggling to get up, at the same pace." You can't rush it. Because you need the reactions in real time.

The actors were incredibly patient with me, and delivered great performances, given the circumstances in which they had to work.

Do you make the entire film in South Africa?

Yes, we shot everything in Cape Town. That helped very much with the budgeting. I don't think we could have afforded to make this film if we had to go to Nevada. We were lucky to find a place where we could build sets in the desert, which is very similar desert to what you find outside of Las Vegas. We constructed the ground control stations on the side of a runway at an airport out in the desert. In the background, we built with CG more of the base that looks like Creech Air Force Base. Most of the background, the land and mountains in the distance, is real. But the fences and the hangers are drawn from images of Creech. To make photo-real CG is almost more challenging than to make fantasy CG.

In addition to Barkhad Abdi, a Somalia-born American actor, you worked with actual Somali refugees.

There are many black South African actors, but they don't speak Somali. Their features are different. Somali people have a very distinct look. And there are thousands of Somali refugees in Cape Town, who fled the fighting. Al-Shabaab made their lives utterly miserable.

The actors who played the parents of the young girl are in fact married. She's a singer; he was a performer. Al-Shabaab banned music, and shot his brother. It was very sobering hearing their stories.

The little girl is also a refugee. Her mother is briefly in the film, buying bread. The little girl in green is her sister. And the little boy who runs to get the bread at the end is her real brother. The family is actually seeking asylum in the United States.

I worked with them for about four or five weeks in rehearsals to help them understand the acting process. I'm very proud of the performance of that group, because I think they measure up. When you're up against Helen Mirren, you don't want a bad performance.

And they have the advantage of not working against a green screen.

Very good point. There were working in a more real environment. And that's not a CG explosion. That's a real explosion. There's something about seeing a real explosion that gives you a proper sense of what a Hellfire missile does.

There are a lot of effective contrasts in the film, and one of them is the pacing. Between let's-do-this-now and oh…the…girl's…still…there.

Yes. I hope that builds the tension and frustration, and allows you at moments to even laugh. When you have actors as good as Helen Mirren and Alan Rickman — and Jeremy Northam and Iain Glen — they allow you to laugh. Especially Alan. He's just a master of giving a twist to a line, or a roll of an eye, that allows the audience to release with laughter at the craziness of the situation and then come back. So they're not on just one note the whole way through.

Rickman was a master of exasperation.

Yes, he was. Also, when you're doing a film that is very much driven by the story, and you've got multiple characters approaching the story from multiple points of view, you don't have a lot of time to set up backstories for the characters. You need very economical writing to give you just enough information so that you can bond with the character, but then you need an actor who, with minimal material, can give you maximum character. So Alan's moment with a doll tells you everything about this man, but only in the hands of an actor who can deliver those layers.

I think that's a credit to Guy Hibbert's screenwriting. It's extremely accurately researched. A lot of people do wonder if it's real. And the answer is, yes, yes, yes. In fact, the danger with our film is that we're probably going to be out of date very soon. Because the tiny drones are now being weaponized. The next phase is face-recognition software in those tiny drones. You can go on TED and see the tiny drones flying in swarms already. They know where they are in relation to each other. There's so much of this technology that we just couldn't cram it all into the film.

There are hundreds of different kinds of drones already. We've got three. Hopefully, there's enough in the film for people to understand where this technology is going. So we can focus on the moral questions that the film raises.

There's lots of information about drones available. But some of it must be classified.

Exactly. You can buy tiny drones now. I've seen a friend's kid playing with a little one that probably cost $20. They're everywhere. It's how they become weaponized, how they are used from a military perspective, that's the interesting question.

The real question is what will the legal framework be, what will the policy framework be, to govern this strange new world. Technology is ahead of policy. What is the strategy we will use to employ these weapons? That's the conversation that is really happening within the military. A lot of people think the military just has one view. They don't.

There are more drones now than fighter aircraft, by a long way. And they are training more drone pilots than fighter pilots. Where this is going, I don't know. But when I read Guy's script, it drew me into a world that I didn't know a lot about. I was initially very skeptical. Is this real? I didn't go and see Colin Firth and Ged Doherty, the producers, for a month. I said I was really interested, but I would like some time to do some research. Only after that did I feel that, OK, we're going to be making a film that's rooted in where we are.

You mentioned Colin Firth. Before the film was made, he was reported to have the lead role.

At one point, I was really hoping he would. The character Helen Mirren plays was written for a man. At the time I met him, Colin was leaning toward being in the film, but not sure as a producer that he should be. It was his first producing job. I pitched this idea, very nervous about whether they'd think I was nuts, but I said, "How would you guys feel if the character of Col. Powell was played by a woman?" They only took a few seconds, and then thought it was a really good idea. I didn't know if I'd lose the job over that question.

I felt that Helen would bring this steely intelligence to it. More importantly, I thought it would give us an opportunity to broaden the conversation. When you make a movie that's just a whole lot of men at war, I think women can feel excluded. I didn't want that, because there are women doing the job that Helen does in the movie. We researched with those women.

Another interesting contrast is that you have two movies at once. One is a thriller, and the other is a sort of a courtroom drama.

Yes! That's a very good way of putting it. And the audience is the jury. That's exactly right.

I think that's a credit, once again, to Guy's writing. How do you hold an audience in the cinema who comes to be entertained? This is the movies. This is not homework. So how can you give them an edge-of-your-seat experience and also give them something to talk about? That is why every argument in the film, Guy and I went back and forth on. Let's try to pull in all these complex arguments, but let's try to do them as efficiently as possible.

I'm a lawyer by training. You want to make sure that when you put arguments about reasonable use of force in the mouth of that military lawyer, lawyers will feel, "Yes that's right, and not, "Well, you really oversimplified that." But you also want your lay audience to not be lost, or feel bored.

You want to keep the engine going. You don't want to come to a grinding halt. There are moments in the film where you need to slow down enough so that the audience doesn't get confused. That's not just a writing question; it's also in the editing.

What we hope with the film is not that it tells you what to think, but that it presents, visually, touch points from which conversations can spin off. Aaron's character says, for example, "I'm the pilot in command responsible for releasing this weapon. I will not release my weapon until you rerun the [collateral damage estimation]." That is a real line that drone pilots are trained to say when being put under pressure to execute an order that they believe is not legal.

It's very important that they understand that, because they swear not to obey all orders, but to obey all legal orders. All soldiers know, or should know, that each of us is required to actually make a judgment. That's so contrary to what we think about the military: It's all about following orders. But if you follow an order that's illegal, you will be held accountable. That's an amazing amount of pressure on a 24-year-old pilot.

Did the producers know you were a lawyer when they brought you this script?

[laughs] I don't know. They may have.