Industrial Light & Magic’s Cody Gramstad on Painting Lucy’s World

There have been plenty of spectacular special effects to feast on this summer, which has really been the case every summer since the blockbuster was invented. Edge of Tomorrow offered Tom Cruise and Emily Blunt on a time-looped platter for voracious aliens, while Guardians of the Galaxy’s glorious, color-soaked space epic includes the spectacle of a gun-toting raccoon and a sentient tree-person that feeds off the flowers that grow on his own body. It’s good stuff. Yet perhaps no film this summer has offered such a surreal, and gorgeous, special effects palette than Luc Besson’s Lucy. And the arresting, original effects, produced by that powerhouse SFX studio Industrial Light & Magic, were created in large part thanks to the use of illustrators and artists from all manner of backgrounds coming together to make a uniquely blissed out, bizarre and beautiful world of color and light.

“I come from an illustration background, and like a lot of us I was brought in for specific reasons,” says Cody Gramstad, one of ILM's resident artists. Gramstad was hired because of his abilities with a stylus and Photoshop, not any of the heavy duty computer graphics ILM is known for. “Lucy was such a unique project, we had SFX people come in from Germany to work on particles, and we had traditional painters come in, too.”

Scarlett Johannson is Lucy, a young American student in Taiwan who gets herself mixed up with some sinister-types who force her to smuggle a precious new drug they’re selling—inside her body. When the drug leaks, Lucy finds she’s able to harness increasingly larger percentages of her brain. Forget that scientists long ago debunked the “10 percent myth,” what’s important to Lucy viewers is how incredible, and incredibly different, the effects of Lucy's growing brain power are in Besson’s fever dream of a film. With every uptick in brain percentage, Lucy goes from being able to see the subatomic world all around her to being able to manipulate it. For Gramstad his fellow ILM artists, this meant creating a world in which trees glow with subatomic life, phones spew coded trails into the sky and even her enemy's thoughts can be seen, touched and changed.

Because most projects at ILM are live-action based (Transformers, Pacific Rim, etc.), there is a lot of heavy-duty effects work to do from artists who have very specific roles. For Transformers alone, we spoke to SFX supervisor David Meny, creature supervisor Michael Balog and the FX technical director Sheldon Serrao. These guys had teams of people working for them on their specific, crucial components of the film. As wild as what’s happening on screen is (gigantic alien robots riding atop gigantic alien robot dinosaurs in downtown Hong Kong), it’s still live-action, created to look concrete and real. In fact, Sheldon Serrao was in charge of making sure when a Transformer clobbered a building, the concrete he smashed exploded into particulates that looked authentic.

For Lucy, the effects are much more abstract and, for lack of a better word, artistic. “Lucy sees the world differently,” Gramstad says. “After being affected by this drug, the aesthetic became more illustrative, and what we created didn’t need to be realistic but stylized, so we branched out from a lot the work we usually do at ILM to create Lucy’s specific look.”

Gramstad doesn’t have the usual background for someone working at a SFX house like ILM. “I did mostly short film and advertisements,” he says. Richard Bluff, the visual effects supervisor, found him online and recruited him. “I have a good understanding of light and color, and we were able to work together easily. Lucy was a small team sharing a lot of dialogue, and we were able to brainstorm and come up with ideas. At ILM, they feel if you have artistic sense, they can teach you the technical side. I’m in training here to become technical artist, but a lot of what I did for Lucy was talking with our team and painting.”

Although ILM is usually very specific about their job descriptions, because of the way Lucy was conceived and shot, with Besson coming up with new ideas on how he wanted what Lucy saw to look while he was filming, Gramstad said they couldn’t build a team like that. “Our team was built primarily of generalists, people with a broader knowledge, so we’re able to have a small team of people who do more things. While I did paintings and shot work, even people doing particle effects would pitch concept ideas, looks, and aesthetics—everybody had to be an artist and a technician.”

Lucy has the look and feel of something lovingly crafted. “I come from an exaggerated style and cartoon background, and though the movie isn’t cartoony, we pushed saturation and color more in this film then we typically do,” Gramstad says. “I took realistic lighting and pushed it in certain ways to make it more appealing, but we kept it within a realm of reality that we can understand.”

When a film relies heavily on the perspective of a changing character like Lucy (much like Neo in the Wachowski siblings’ original The Matrix), we need to both understand what it is we’re seeing while also being swept away by the novelty of this new world. Gramstad needed to track the changes in Lucy’s burgeoning powers in subtle but significant ways. “We build and progress her powers, so the style changes as the movie goes on,” Gramstad says. “It starts with subtler effects, like with glowing elements coming out of a tree as she can actually see the life within that tree. Later, we get to a point where [what she sees] almost becomes abstract, the audience isn’t meant to understand—it’s only on Lucy’s level of understanding.”

Through Lucy's Eyes

The Computer Tower

"Many of the ideas for the film were already started by the talented client side concept artists, so my job then became to evolve those ideas as Luc's vision changed during production. The above is an example from Lucy's computer tower. The original concepts were much more organic, they had an almost liquid feel throughout the tower. However, as they shot the sequence, Luc felt as if we needed a solid foundation for Lucy's tendrils to build around, so we developed this design based on an odd mix of tendrils, obsidian and an office tower. This concept was mixed with the original client side concepts to lead to the final design in the film."

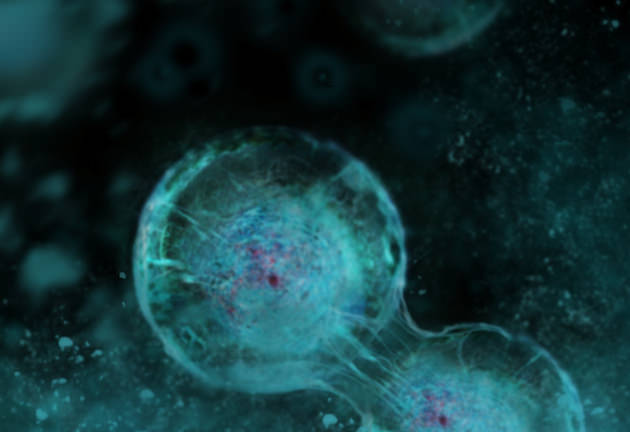

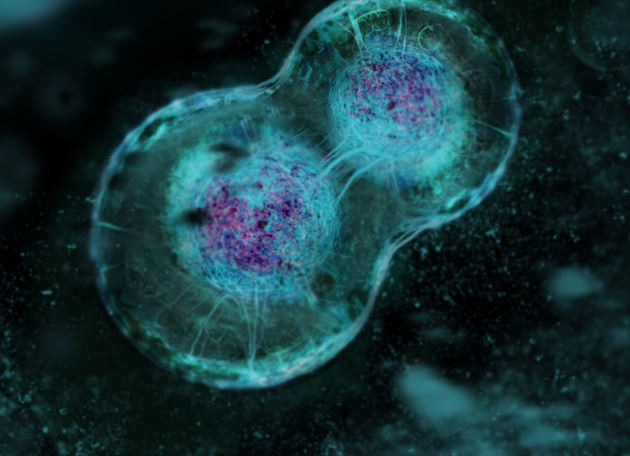

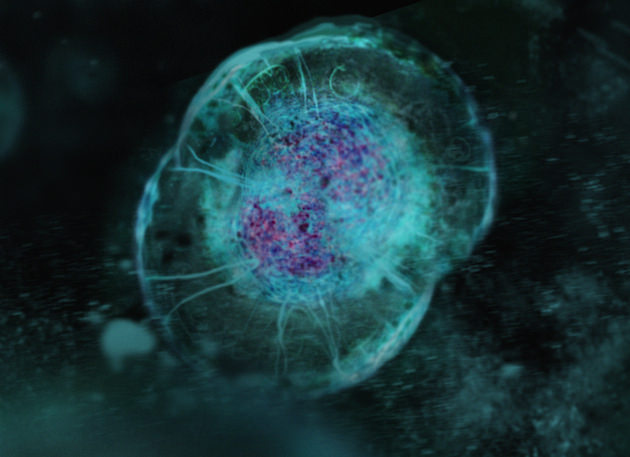

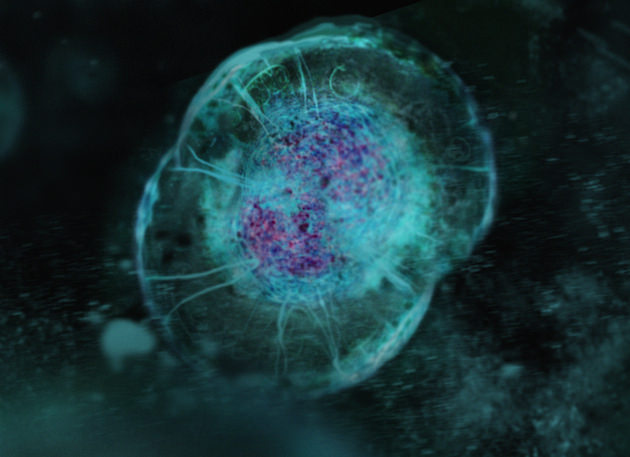

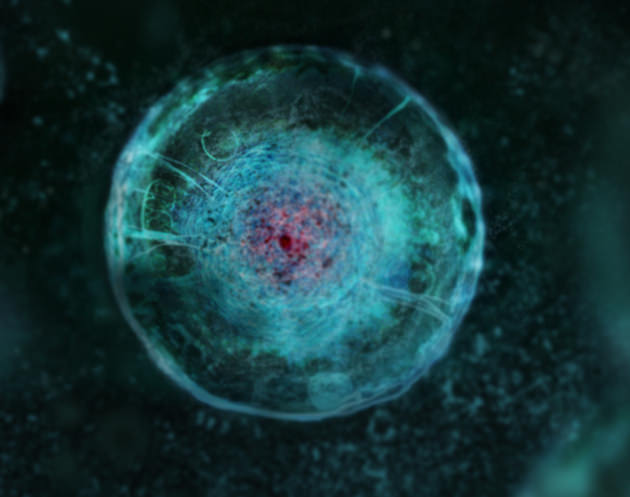

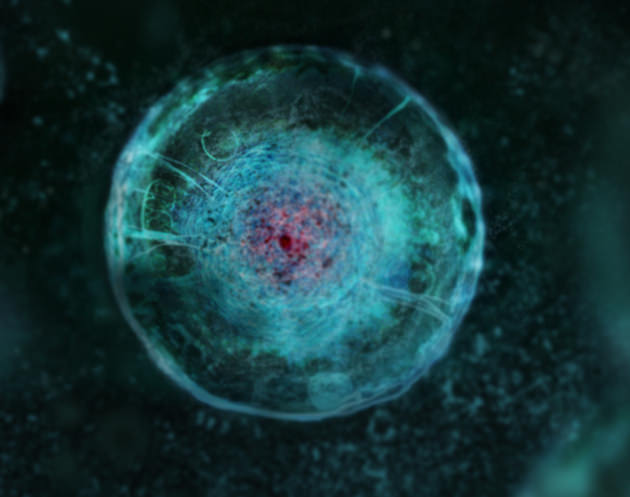

Cells

"Luc had requested a sequence of cells going through mitosis as a tool to help bookend his story. He wanted them to be both recognizable as cells but also slightly foreign in their design, as if the audience was viewing something familiar through Lucy's new perception of the world. To do this, we based the designs off specific images that we found of the Helix Nebula. The cells exist in a relatively monochromatic environment, however, as they begin to reproduce we reveal a hidden red core to add sparks of interest as the cells multiply. Our hopes were that by merging these looks, the cells would feel appropriate as both organic in the beginning of the film and abstract at the end."

For his work, Gramstad keeps it fairly simple. “I need a Wacom tablet, Photoshop and a stylus,” he says. “We use a mix of off the shelf software that’s been adapted to work for ILM, plus proprietary ILM software. We run a huge gamut of programs.”

Part of Gramstad's process is grabbing references for their work. “One is Matthias Müller, the German effects artist, another is Perry Hall, a traditional live painter who uses oils and paints and sounds and vibrations to create moving paintings. So some of my process was absorbing all these different references and start filtering it. Then I started doing full color storyboards, using our different sources, and then pitching them to Luc to see if it worked well for him. So we work on our early concepts, collect ideas, and then once we filtered it all through Luc and got an understanding of the aesthetics he wanted, then we carried it all through and built the shots.”

Gramstad's experience of working with Besson was perfectly suited for a illustrator becoming a technical expert as well. “Luc has his clear vision, but what’s great about him is he’s one of those guys who gets so excited about the project and about new ideas,” he says. “We kept the ideas within the realm of what he wanted, but there was room for adaptation, especially for a film like this that’s abstract in a way, it was malleable. It’s very unique, you don’t usually get directors like that and who are willing to listen to ideas.”

Gramstad did his digital painting primarily on photoshop. “For some of the early references, I’d do really quick storyboard, maybe fifty small paintings to get an idea across,” he says. “Sometimes, because the work is so abstract, it might just be blotches of color, or the mood or movement in sequence. Once those are settled and it feels right to Luc, then I work with a specific artist building the shot, discussing with them how it should look. When it’s abstract, it’s difficult to portray in a single painting how the shot should look. In a way, every single effects artist had to be a designer, they had to take these shots in this relatively simple conceptual form and make it as interesting as Luc wanted. My job was sitting down with them and discussing how we were going to expand a simple painting or photo reference into the huge world Luc is creating.”

As much of an artistic process as this was for Gramstad, it wasn't the most important part. “One of the biggest things I contributed was just communication—while my paintings were helpful, especially in Lucy’s abstract world, that’ll only get you so far. A lot of this process was sitting down and working creatively with everybody to pitch and build ideas, and it’s the part of the job I enjoy the most. How are we going to build it, and how will it look?”

Featured image: Lucy's eye, courtesy Industrial Light & Magic.