From Making Hats to 3D Cats: Self-Taught Animator TJ Nabors Helps Create The Croods

TJ Nabors has taken your typical road to becoming a top animator in Hollywood—she started out designing hats. She was in theater at the University of Texas, and was focusing on textiles and costume, when she took a particular shine to the creation of hats. "There was a distilled and theatrical power to transform the wearer," she says. The power to transform one thing into another would become a theme in Nabors professional life, as she transformed herself into a self-taught animator, and, after years of honing her craft, is now one of the wizards behind DreamWorks Animation's upcoming film, The Croods, which premieres on March 22.

Nabors has been working on The Croods, about the “world’s first modern family,” as DreamWorks puts it, for a very long time. Every animated film, especially one rendered in 3D, takes hundreds of artists many years to make. The painstaking level of detail required for every inch of the screen, every eyelash, whisker, ray of light and shadow you see, is astounding.

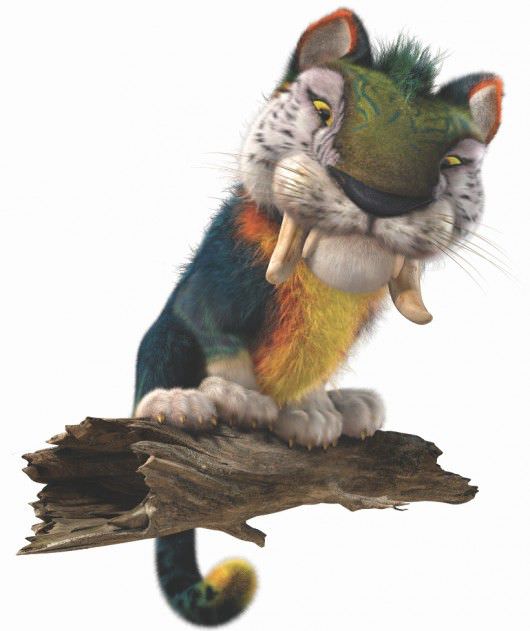

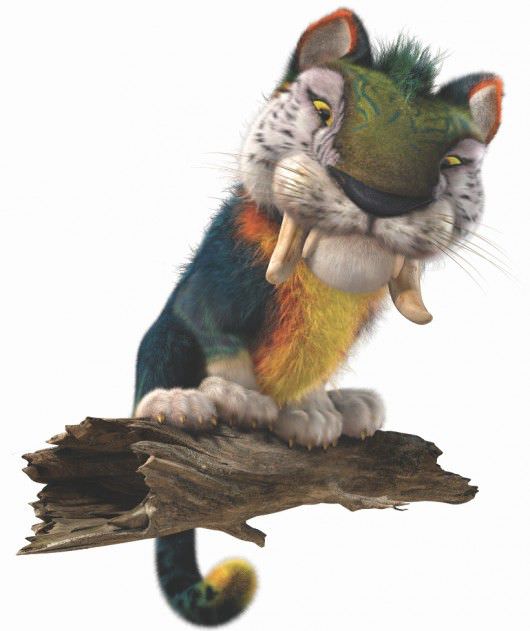

The film follows the family Crood as they are forced out of the cave that has been their home for their entire lives, and tasked with venturing into the wider world, filled with fantastic creatures (one of which, a colorful tiger-like beast called the 'Macawnivore,' was Nabors very own pet project, as it were). The film follows the trials and tribulations of this family as they are besieged by the drama of the natural world as well as the drama inherent in any family road trip. The rebellious teenager and the precocious toddler are entities as powerful as any of the beasts they encounter. The voiceover work was done by stars such as Nicolas Cage, Emma Stone, Ryan Reynolds and Catherine Keener; while the characters they voice, and the incredible world they inhabit, was done by hundreds of lesser known stars, such as Nabors.

We spoke to Nabors, a Texas native now happily residing in Los Angeles, about what inspired her to go from a hat designer to an animator, what Debbie Harry and Andy Warhol had to do with it, and what she did as a surfacer on the upcoming The Croods.

The Credits: So how exactly did you go from designing hats to designing three-dimensional digital creations?

Nabors: While making hats, I became interested in the computer's ability to create images from the moment I saw a NOVA program on the possibility in the 70's. All the resulting images looked, at a distance, like Chuck Close paintings— big old pixels—but I was enchanted with the idea and the process. The principles of computer imaging are so close to those of my first love, textile production, which found its expression in the hats. The 18th century jacquard loom was crucial to the development of the computer, the inspiration for the storage of information on punch cards. The connection, for me, represented a logical, conceptually romantic and exciting next phase. As soon as personal computers became capable of creating images, I found myself taking informal classes and struggling to get my hands on any computer I could find.

What kind of computers were capable of animation back then?

In 1985, the Amiga computer was launched at a black tie event at Lincoln Center, which featured an appearance by Deborah Harry and, especially, Andy Warhol, who sat down at the Amiga and painted an image of Ms. Harry, though he'd never touched a computer before (the video still haunts Youtube). The little machine was a wonder. It debuted with the capability to support basic animation, sound and video and it was priced within an artist's reach. Sadly, it ultimately didn't withstand development competition from Mac and PC, but it bridged the careers of many artists who went from traditional to early digital mediums.

That’s unbelievable. Warhol plus Debbie Harry plus a computer—we totally get how you were enchanted.

The Warhol debut had me hankering mightily for an Amiga to call my own. A friend, a child development specialist who worked for Word Publishing, provided the opportunity. Her first media project was to be a video that stimulated and guided innate perceptual development patterns in very young children. She wanted elements that moved in a flat plane across the screen, which were first predictable, then mildly surprising (the peekaboo effect), in saturated color. As a total amateur, my compensation for designing and creating the animation was an Amiga 500. There was no hard drive—an enormous amount of information was saved (and lost and saved again) on floppy disks. In the end, it was probably the hardest, most poetic work I've done.

What did those animations look like?

The animations included the rising of the moon, the swell of bubbles, the falling of leaves, the opening of flowers, the slow raising of window shades to reveal some little delight behind. The work was very 2D and very hand wrought. I had to discover for myself the most basic principles of animation. The project was a great education, and I was hooked. Though my back and brain ached from the process, computer imaging was all I wanted to do.

So with the seed firmly planted, how do you go from creating 2D bubbles to being an animator at DreamWorks and creating incredibly complex images like you did for The Croods?

Eventually, after years of developing animations for ever more sophisticated industrial films, then commercials, then PBS special features, I partnered in a company to create interactive projects. The first was for the Department of Energy and traveled to museums around the country. The next was an interactive CD Rom, targeted to young girls, on the evolution of horse breeds as a window onto world history and culture. It was very beautiful and won awards including the Outstanding Achievement Award at South X Southwest Film and Interactive Festival. Even before it was released, I was recruited by Will Vinton Studios, now Laika, first as a technical director, then as an art director.

How long were you there and what did you do?

After five years there, during which I did Super Bowl commercials, short film, and art directed a TV pilot, I was hired away by DreamWorks, where I've been senior surfacer since 2002, minus a two year leave to accept the Rudd Endowed Chair in the Moving Image Arts Dept. at College of Santa Fe (now Santa Fe College of Art and Design). At DreamWorks, I've had the pleasure of being an integral part of three Shrek films and a Shrek TV special, and then the visually stunning The Croods. I'm currently working on the sequel to the Oscar nominated How To Train Your Dragon.

I think people have a very skewed view of what people who work in the CGI field are like—you clearly break the mold, coming from hat design, what else don’t we know about you folks?

There exists the assumption in the world that computer graphics are created by the push of a button, but nothing could be less accurate. CG animated films are created by skilled and passionate artists, and, though consistency is mandated by the production designer and art director, the mark of the hand and of individual sensibility is present in every frame, and not only individual sensibility, but the blend of craftsmanship among dozens of artists to create a truly collaborative work.

What does a surfacer do, exactly?

My particular work is painting the surfaces of flat grey models— geometry created in the computer by the modeling team. I paint not only color, but all the material properties. Hand painted maps guide the way light falls on an object—its specularity, areas of sheen, matte and everything in-between; transparency, translucency and sub-surface properties-the way light bounces through some materials (such as skin) and back out at an oblique angle, vaguely revealing the layer below, reflection, refraction, along with dirt, wear and degradation. We build in dimensional details of the object with bump and displacement maps. A simple object is defined by hundreds of individual maps which must be created by painting directly on the object within the computer.

Wow, the level of detail is astounding.

I also create fur and hair, which require dozens of maps of their own. Producing a credible material is quite complex and requires the development of minute habits of observation and analysis as well as the ability to conceptually shatter a material into its component elements. I have art direction and usually some concept art as a guide, but the individual artist has the latitude of his or her own understanding, state of mind and interpretation of the material. Most certainly, that understanding is subject to the critique of the designers, but the mark of the hand is ever there. To watch an animated film is to see thousands or millions of paintings applied to surfaces and in motion. When an audience watches an animated film, they're looking into the personal lives and souls of the artists who do the work. That's what makes our days worthwhile on a personal level.

That's a beautiful way of putting it. How has your job changed in the last few years with the increasing sophistication of technology?

The era of the self-taught animator has really faded. This work today requires an ever greater understanding of a madly evolving technology. One is no longer an artist or a technician. One has to be a left and right brain creative. The young DreamWorks artists have typically come out of graduate programs. They have remarkable understanding of the technical aspects of production as well as craftsmanship and soul to spare.

What advice would you have for someone who dreams of one day working at a DreamWorks or a Pixar as an animator?

I'd say that, though technology changes, and work flow mutates, the young artist who finds her creative center and produces early work with a distinctive voice will always be noticed and rewarded. And, above all, that artist will have found the profound satisfaction of producing work of originality and self-expression that will sustain him or her for a lifetime.

You mentioned that sometimes hundreds of artists working on a single film. One of the issues we touch upon here at The Credits is helping to protect the content of creators, be they production designers, composers or animators. Can you tell us your thoughts on protecting content?

On the issue of piracy, box office receipts are diminishing. The cost of the years of work and support of literally hundreds of artists' families that go into creating an animated film make any such project terribly vulnerable to market forces. For our corner of the industry, piracy has dreadful consequences. In addition, I took my horse trainer and his young, quiet helper to the opening weekend of How To Train Your Dragon in 3D; because, being trainers, I thought they would be delighted by the story and the 3D experience. Sadly, after the movie began, the young man confided that he already had a bootleg DVD and had seen the film. To his great loss, the magic of the thrilling and beautiful film was unavailable to him, because his view was colored by the exposure to a ragged, pirated copy on a tiny screen.

Featured image: MACAWNIVORE- With the body of a small tiger, an over-sized head and the colorization of a Macaw Parrot, the Macawnivore is an imposing creature who towers over the Croods. Image courtesy DreamWorks